The Inquisitor Review

Praying in Vain

Mordimer Madderdin arrives in the town of Koeningstein to investigate reports of a vampire. However, witnessing the innkeeper suddenly despawning after our first conversation tipped me off that even stranger things might be afoot. But instead of giving me the tools to unravel the interconnected threads of an intricate mystery, The Inquisitor insisted on firmly holding my hand, forcing me to watch as it buckled under the weight of its ambition.

Based on Polish author Jacek Piekara’s works, the alternative history it proposes easily draws you in. You take on the role of the titular inquisitor, an agent of a version of Christianity that values vengeance instead of turning the other cheek. Dashes of the supernatural embellish its grim realism, but the setting remains mostly grounded in medieval European history, which is a nice touch.

Unfortunately, The Inquisitor doesn’t make a great first impression; or second; or third. Low production values across the board make it look and play like a game that came out two decades ago, deeply hurting immersion. Whether you’re walking the narrow muddy streets of Koeningstein’s poorer districts or exploring its lavish cathedral, you pass by ugly NPCs who perform limited routines.

Many of them simply stand in place, awkwardly gesticulating as they mimic non-existent conversations. At the same time, guards who aren’t out on short patrols sometimes adopt a stance that resembles a halfway T-pose. Despite being visibly populated, the town never quite feels alive, even when you pass by bigger crowds.

During dialog sequences, interlocutors always attempt to pierce your soul with their unnatural android-like stare while stiff facial expressions make it hard to focus on the often-stunted conversations. The few times cutscenes show characters drinking, they do so in a manner that clearly betrays the lack of liquid in their glasses. It’s a small complaint that could have easily been addressed by slightly adjusting the camera angle, but one of many that add to the pile of immersion-breaking issues plaguing The Inquisitor.

Attempt to venture into the town’s hidden corners – not that there’s a lot to find aside from collectible texts that, only on a few occasions, reward you with a chuckle for your efforts – and you might end up stuck in the level’s geometry or behind a group of people you previously had no trouble walking by.

Entering new sections of the town is also a hassle. After approaching the gate and interacting with it, you have to sit through short cutscenes that show Mordimer walking up to that very same gate or strutting away from it. And, no, the ability to partially skip them doesn’t make this any less frustrating.

Other cutscenes don’t fare any better, turning would-be intense duels into awkward fights that see characters weightlessly flailing their limbs and weapons around. Too often, a mixture of clunky animations, writing whose quality varies wildly, and inconsistent voice acting infuses involuntary comedy into situations that aim to be dramatic or pivotal to what’s intended as a dark fantasy narrative.

The closest The Inquisitor gets to an interesting, almost terrifying figure is when you’re trapped in the town’s dungeons alongside a rhyming executioner who’s gone insane. Consistently creative lines feed into his deranged nature, but the sequence otherwise plays as jankily as everything else.

Staying too long in darkness while chasing him down renders Mordimer vulnerable, but torches are spread too generously around the dungeon, rendering this mechanic effectively useless. The moment when the hunter becomes the prey is ruined by clumsy cutscene work and limp quick-time events, while the final chase sequence is laughably bad due to how this seemingly implacable foe adopts the speed of a cartoon villain that must allow the heroes to escape.

You spent a good chunk of your time walking through an unremarkable play space that, despite having all the elements of a proper city and sporting a decent amount of visual variety, never feels like one. Its sections aren’t too expansive and, although signposts indicate that, at some point, organic exploration was considered, the inclusion of the Prayer mechanic removes any need for it, by pointing you towards the next objective 90% of the time.

When used, the screen turns pitch black as it marks your objective with a tall golden beam while highlighting the silhouettes of important NPCs and collectible items. This essentially removes any need to explore yourself, not that doing so would yield any satisfaction.

The Unworld encourages stealth but most enemies deal little damage while falling to a few sword strikes.

The Unworld encourages stealth but most enemies deal little damage while falling to a few sword strikes.

The story is structured all too conveniently, pointing you in the right direction without much effort on your part. Getting invested in its muddled mystery is a tough ask when you move so quickly between seemingly unrelated events. It also doesn’t help that the people you meet rarely have anything genuinely interesting to say.

What little detective work remains is equally underwhelming due to a series of fitting but ultimately rudimentary mechanics. When examining bodies, you simply need to move the camera around until you find the right angle, which prompts Mordimer to perform a dry monologue. Eavesdropping puts you in control of a disembodied camera that sometimes enables you to listen to bland conversations that you shouldn’t normally be able to hear.

The Inquisitor also sprinkles in a few simple puzzles that can be brute forced, while its obtuse choice system seems bereft of consequence. You can freely alternate between brutalizing children and being compassionate towards other citizens without having to worry about anything at all, including notable changes in Mordimer’s personality or how others treat him.

Equally slapdash, combat lacks any sense of weight or impact. If, while walking, Mordimer turns with the nimbleness of a loaded truck, during duels he floats, albeit not quite like a butterfly. He does at least sting like a bee, since you can quickly defeat the vast majority of enemies by spamming your light attack.

There’s little finesse involved – despite the presence of dodges, blocks, and perfect parries – which makes The Inquisitor’s battles exceptionally tedious. A poorly designed final encounter then asks you to spend the vast majority of time waiting around and dodging slow attacks, before hoping that – during brief vulnerability windows – your hits register against the enemy’s imprecise hitbox.

Whenever you approach a narrative impasse and lack answers, convenient visits to the Unworld are both a universal solution and as major a crutch as the Prayer mechanic. This otherworldly plane of existence is Mordimer’s secret weapon, allowing him to conveniently retrieve shards of the truth whenever he needs to piece together things.

This involves repeatedly exploring several islands connected to a central point in the Unworld while avoiding enemies and a flying monster named the Murk. Although the gameplay evolves between repeat visits – in, perhaps, the most unexpected twist –, these stealth sections are functional but poorly put together.

Mordimer can use supernatural abilities that grant slower detection or allow him to bypass hazardous areas, but I picked up most of the shards by casually running around enemy vision cones. If the roaming shadowy figures do spot you, they fall to your sword as easily as regular peasants, removing any tangible sense of threat or challenge.

Opponents fight as if they'd rather not be there, making spamming light attacks the most effective strategy.

Opponents fight as if they'd rather not be there, making spamming light attacks the most effective strategy.

During later visits, the Horsemen of the Apocalypse begin launching volleys of arrows that give you generous amounts of time to get out of the way. Then, one blocks the paths connecting the islands with a massive sword.

It’s an imposing sight that establishes the horsemen as a threat for a few moments, until you realize that you can negate this massive obstacle by waiting for a few seconds for it to unceremoniously despawn, much like the innkeeper; the mechanic serves no other purpose than to waste your time.

Should you somehow get spotted by the Murk, it does quickly drain your health. However, the lack of an actual death animation – replaced by two seconds of Mordimer running around as if nothing happened before the game over screen sends you back to the previous checkpoint – reminds you, yet again, that immersion is a luxury few can seemingly afford.

Performance

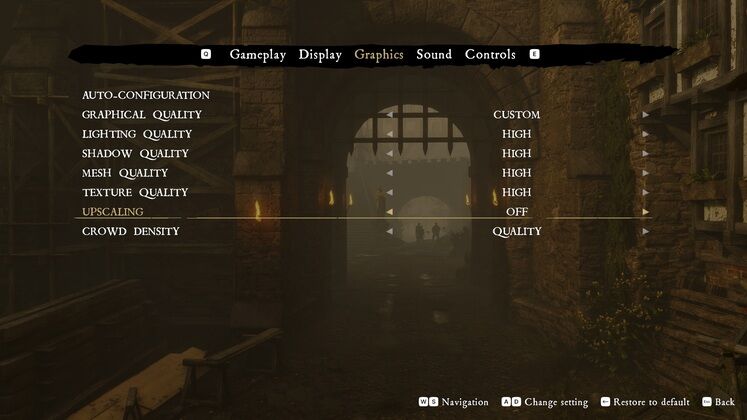

On an i7-13700K, 32 GB RAM, Nvidia RTX 3080@1440p, The Inquisitor ran mostly fine. Yet, despite looking like a game that could have realistically been released on the PS3, I did notice a few loading stutters and saw my framerate drop to 30 in more crowded areas, at least when not using upscaling tech such as DLSS or FSR. Unfortunately, the quality setting of both tanks the image quality by adding a strong blurring effect.

THE INQUISITOR VERDICT

Woefully dated, even for a game that inhabits the deepest of eurojank mires, The Inquisitor fails to live up to its captivating premise at just about every step. Obtuse choices, stiff facial animations, and uneven voice performances rob its protagonist and supporting cast of any semblance of personality. Clunky animations and ugly character models then infuse involuntary comedy into moments otherwise intended to be dramatic, while uneven writing underpins a muddled mystery that relies far too much on convenience to push things forward.

Mechanically, The Inquisitor borrows from several genres but rudimentary implementation fails to make a case for engaging in clue collecting or swordfighting. Worse yet, some of its mechanics are only there waste your time. On paper, and with more work put into it, The Inquisitor could have been a decent low-budget romp through an interesting setting. Sadly, in its current form, it only succeeds as a contender for the title of worst game of the year.

TOP GAME MOMENT

Meeting the insane rhyming executioner inside the town’s dungeons.

Good vs Bad

- Functional and relatively short

- Dated visuals

- Clunky animations

- Weightless combat

- Too much hand-holding

- Confused plot, forgettable characters

- Lack of challenge and atmosphere